SERBIA – HOMELAND OF ROMAN EMPERORS: DECIUS TRAIAN (249–251)

A Man from Srem under Roman Laurels

A line of Roman emperors originating from the Balkan provinces stepped to the throne from mid-III century, “when the crisis of the Empire entered a dark, irreversible apogee”. There were eighteen of them (if we also count the two early-Byzantine ones). They were born in the areas of Pannonia Inferior, Upper Maesia, late-Antique provinces of Dacia Ripensis and Inner Dacia, now within the Serbian borders. The first millennium circle of Rome has just been closed, the cohesion forces weakened, the foundation values were shaken. “Simple, toughened in poverty, brave, raised with the elementary feeling of honor and faith, bringing the original genius loci of this soil, a heritage of great memory, each of them built their military careers on basic Roman ethical postulates: pietas, devotio, fides. The living force and firmness which the Roman Empire was loosing for good, was recognizable in them.” Faithfully serving the Empire – says Milan Budimir – they deserved to become rulers from subjects and dress the efforts, hardships, diligence and sacrifice of generations of their ancestors into imperial purple and scarlet, as a divine reward and satisfaction. That very relation with the roots they sprouted from returned them, in an Antaean way, to their birth soil, where they searched for eternal peace and memory. The National Review will, in each issue, in chronological order, bring stories of all Roman emperors originating from the area of present Serbia, written by Professor Aleksandar Jovanović (Serbia – Homeland of Roman Emperors, “Princip Bonart Press”, Beograd, 2006)

Written by: Prof. dr Aleksandar Jovanović*

The honorable destiny of Decius, whose full name was the ceremonially long Caius Messius Quintus Decius and invoked his Pannonian origins, was determined by Mars with the Emperor’s birthplace. Decius was born in the village of Budalia, a place 8 miles west of Sirmium in the direction of the setting sun. The name Budalia originates from an epithet attributed to Mars, with a testimonial in the Celtic cultural milieu. Several other monuments also testify to Mars’ influence in this region. An inscription from Rome mentions Aurelius Verus, a soldier of the Praetorian Guard, who came from Pannonia, the region of Sirmium, village of Martio and hamlet of Budalia. A similar inscription exists on a tombstone that Aurelius Maximus raised to his brother. Aurelius was a legate of the Adiutrix I Legion and came from Pannonia Inferior, the village of Martio and the hamlet whose name was only partially preserved – only its final portion: “…diano”, which probably comes from (Candi)diano that could be also related to another epithet attributed to Mars. It seems that a larger village (pagus) existed in this area and it probably evolved into a civitas dedicated to Mars and named Martius. This township comprised several hamlets (vicus), all having names derived from Mars’ epithets (Budalia, /Candi/dina). Budalia probably stood at the location of the present village of Kuzmin, whereas the ancient name of the pagus Martius still lives in the name of the present village of Martinci near Kuzmin. The honorable destiny of Decius, whose full name was the ceremonially long Caius Messius Quintus Decius and invoked his Pannonian origins, was determined by Mars with the Emperor’s birthplace. Decius was born in the village of Budalia, a place 8 miles west of Sirmium in the direction of the setting sun. The name Budalia originates from an epithet attributed to Mars, with a testimonial in the Celtic cultural milieu. Several other monuments also testify to Mars’ influence in this region. An inscription from Rome mentions Aurelius Verus, a soldier of the Praetorian Guard, who came from Pannonia, the region of Sirmium, village of Martio and hamlet of Budalia. A similar inscription exists on a tombstone that Aurelius Maximus raised to his brother. Aurelius was a legate of the Adiutrix I Legion and came from Pannonia Inferior, the village of Martio and the hamlet whose name was only partially preserved – only its final portion: “…diano”, which probably comes from (Candi)diano that could be also related to another epithet attributed to Mars. It seems that a larger village (pagus) existed in this area and it probably evolved into a civitas dedicated to Mars and named Martius. This township comprised several hamlets (vicus), all having names derived from Mars’ epithets (Budalia, /Candi/dina). Budalia probably stood at the location of the present village of Kuzmin, whereas the ancient name of the pagus Martius still lives in the name of the present village of Martinci near Kuzmin.

Namely, Decius was born in the period between the II and III century A.D. on the territory that belonged to this domain of Mars’ cult. His father was also a child of Mars. He came from this region and was an army officer, perhaps even a commander of the administrative-military point situated on the important road towards Sirmium. Decius’ mother Herenia (Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla) came from an old Italic family with Etruscan origins. Decius, himself, followed the paths of Mars. The beginnings of his career remain unknown; it seems he achieved glory due to his virtues and skillfulness, and between 234 and 238 A.D. he was mentioned as a governor of the province of Moesia Inferior, which was a prominent title achieved through commitment, courage and dignity. He was a highly respected general, particularly appreciated by soldiers who have always admired dedication and loyalty. He proved his qualities in many wars conducted during the reigns of emperors Gordianus III and Philip the Arab. In the civil war in 249 A.D., as the prefect of the city of Rome, he took victory over Philip in the battle at Verona. This town, where fights of this kind reached their final conclusion, was of special significance. The legions acclaimed Decius emperor. The Senate immediately approved this acclamation and confirmed the election of the new emperor. They recognized in him the emperor who was able to unify the interests of both the Senate and the army. Accordance of these two Roman institutions was a pledge of progress and prosperity. They welcomed the new Traian, once the best among the imperators, and ceremonially named Decius after him.

THE CALL OF THE DANUBIAN FRONTIER

The new emperor, Decius Traian, accepted the new function with a sense of responsibility. He improved the economic situation in the Empire, took care of war veterans, distributed donations promised to the people and repaired road infrastructure in the provinces. However, Mars’ fate drew him to the frontier at the Danube, where the enemy became a stormy threat. Knowing this region well, due to his origins and long military service, he was able to prepare quite well for the warfare. He averted leisure common among troops by engaging them to build roads and bridges in our region. He improved the level of military discipline of his soldiers by demonstrating his own actions, sacrifice and responsibility. He was mentioned as a reparator disciplinae militaris on an inscription from the nearby Moesian village of Oescus (village of Gligen in northwest Bulgaria).

He had immense confidence in troops coming from Illyricum whose soldiers were mainly recruited from our territories. This is evidenced by the coinage bearing the inscription GENIUS EXERCITUS ILLYRICIANI on the reverse. He suppressed his enemies on the frontiers of Dacia and obtained a title of restitutor Daciarum, since he rebuilt the province that was once conquered by his great namesake Traian. Related to this are series of coins with the personification of the province of Dacia represented on the reverse. He also had issued the coinage showing the personification of his native Pannonia, through representations of harmony, wealth, and idea of aeternitas, illustrated in the garlands in the figure’s hands.

At the beginning of 251 A.D. a new danger appeared on the frontiers of the Empire, at the lower part of the Danube. The Goths, led by Kniva, crossed the Danube and pillaged, just like in earlier decades, the lands of Moesia Superior, and especially Moesia Inferior and Thrace. They came in two large armies with the ultimate goal to conquer and plunder the cities of Nicopolis, present Nikiup, and Philippopolis, present Plovdiv. With the cautiousness and concern of a soldier, Decius Traian sensed the approaching danger; he instantly sent his elder son Herennius Etruscus, who was a commander of the army of Illyricum and too young to carry a spear and wear armor, ahead to the battlefield and hastened to join him soon. In the meantime, the Goths besieged Nicopolis and sacked Philippopolis committing a horrible massacre of its inhabitants and prisoners. Decius Traian crushed the Goths in the battle near Nicopolis and waited for those who were coming back with stolen goods from Philippopolis. The battle took place at Abrittus, Razgrad in Moesia Inferior. Guided by the familiar changing war luck and by the war shouts of Mars Ultor, Decius Traian defeated two echelons of the Gothic army, and after winning over the third, he and his troops fell into quicksand, desperately trapped and helpless. The bodies of Herennius Etruscus and Decius Traian were never found; but even if their graves remained unknown, their glory was considered divinely significant: they achieved the greatest Roman ideal – they died while fighting an enemy.

TRIUMPHAL ARCHES AND APOTHEOSIS

Nonetheless, the eternal fate and everlasting memory were insured and certain. Across Abrittus, on the left bank of the Danube, there was a famous memorial complex Tropaeum Traiani (today Adamklisi in the Romanian part of Dobrudža), built by Traian in honor to his dead, unburied soldiers who died in the Danube whirlpools and impassable lands during the long Dacian wars from 101 to 106 A.D. Inside this vast empty tumuli, an immense cenotaph, the final resting place of those who died without military funeral ceremonies and weren’t buried, the great armadillo of Decius – the second Traian, found its peace as well. In general, Tropaeum Traiani was considered to be the place of Decius Traian’s apotheosis; the decoration of the tropaeum itself is more similar to the artistic expression of the Late Antiquity than to the Classicism of Traian’s era. Within the fortress of Tropaeum Traiani, Emperor Licinius, who thought of Decius Traian as his ancestor because of his virtues and honorable death, built a triumphal arch – formed as a tetrapylon, probably to pay tribute to this Emperor.

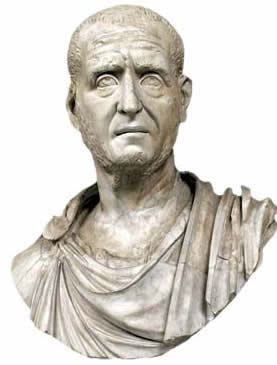

The sculptures representing Decius Traian haven’t been found in our territory. We can make judgments about his appearance on the basis of several busts that were found on other meridians of the Roman Empire and on the basis of his portraits represented on coins. Among the apparently infinite collection of coins, two basic types of portraits representing Decius Traian could be distinguished.

The first type is related to representations on the coins struck in mints in Rome. The emperor is represented in his old age in the realistic style of dynamic expressionism typical for the epoch of the military emperors. His head rests on an elongated neck that emphasizes a certain nobility and dignity in his expression. A military short hair, tall forefront wrinkled by worries and nervousness, sturdy nose showing a Greek-profile, eyes with a look that expresses his compassion and forgiveness as well as his sadness, like on the portraits of many emperors who lived in this epoch. Accentuated cheekbones emphasize the emaciated cheek, which testifies of the Emperor’s military ascetic principles. His carefully-treated beard, longer than the previous Emperor Philip’s, relates Decius Traian to the providence of prudent emperors from the Antonine and Severus dynasties.

A PRISONER OF AN IMPERIAL IDEA

The second type of Decius’s portraits is related to the representations on the coins minted in Mediolanum or, rather, in Viminacium. The portrait looks authoritative but also introvert, tranquil with his tightly pressed lips illustrating non-forgiveness and revenge; the short beard reveals his uptight neck and readiness for action. The second portrait correlates to the opinion of Early Christian authors and apologetics about Decius Traian. This emperor was considered a persecutor of Christians. He broke the pax christiana established at the end of the I century after Domitian’s persecutions. In his work about the persecutors of Christianity, Lactantius explicitly stated: “Extitit post annos plurimos execrabile animal, Decius, qui vexerat Ecclesiam”. Decius Traian is identified with a scornful animal which, after many years marked by wealth and prosperity, plundered the Christian Church.

The persecutions undoubtedly happened. Decius Traian was a supporter of the ancient pagan tradition ever since his youth spent in Pannonia. Thus the persecutions were the consequence of his belief that the official state religion of the Roman Empire was basically the cornerstone of the empire. Solidarity based on these principles was a proven expression of unity and power of the Empire. On the contrary, any spiritual indifference or disagreement could provoke conflicts, reprisals, internal crisis and represent a signal for the external enemies to attack the Empire. In the period that preceded Decius’s time, the Christian community wasn’t large and Christians’ intention to separate themselves from other state institutions was tolerated. However, in the middle of the III century, the number of Christians increased and they represented an important social-economic segment of the Empire. Their proselytism and evangelistic message of world peace they conveyed became a contradiction to Decius Traian’s aspiration to regain the imperial greatness of Rome through the unification of all the subjects of the Empire. Therefore he proclaimed an obligation to respond to the requirements of the official, state religion, that is to say a requirement to offer a sacrifice to the gods during the holidays, although not on dates related to the celebrations of the imperial dynasties. Christians, who in earlier times avoided this obligation by buying fake libelli – certificates of compliance confirming the act – from the corrupted administrative officers, were now faced with a necessity to bring a decision. A smaller number of them, those who were firm in their faith and prepared to face martyrdom, were subject of persecutions.

There was no evidence of significant persecutions organized on our territory at that time. Perhaps the storage of Dobri Do – at the Mesul site near the town of Smederevo, where an unusually beautiful and pervaded with a sacral message extraordinary early-Christian lamp was found (stored right before the approaching danger), hides the secret of the owner who was a victim of this repression and who died in the persecution.

Ancient tradition, as well as contemporary historiography, evaluate the short two-year long reign of Decius Traian as wise, good and unhappily terminated. After Decius Traian died, the troops acclaimed his general Trebonianus Gallus emperor, who ruled together with Hostillian, Decius Traian’s younger son. Shortly afterward, young Hostillian was murdered in the conspiracy organized by Trebonianus Gallus or most likely died of plague. In recent times, the remnants of an imperial funus, which is preliminarily related to Hostillian, were discovered in Viminacium.

(The author is a professor at the Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy.

Prepared and adjusted by: NR)

***

Decius was born in the village of Budalia, a place 8 miles west of Sirmium in the direction of the setting sun, the present area of Kuzmin.

***

The new emperor, Decius Traian, accepted the new function with a sense of responsibility. He improved the economic situation in the Empire, took care of war veterans, distributed donations promised to the people and repaired road infrastructure in the provinces. He averted leisure common among troops by engaging them to build roads and bridges in our region. He improved a level of military discipline of his soldiers by demonstrating his own actions, sacrifice and responsibility.

***

On the coins minted in Rome, the emperor was represented in his old age, in the realistic style of dynamic expressionism typical for the epoch of the military emperors. Accentuated cheekbones emphasize the emaciated cheek, which testifies of the Emperor’s military ascetic principles.

|